Incidence of Diabetes in Children and Adolescents During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Key Points

Question

Was there a change in the incidence of diabetes in children and adolescents after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic?

Findings

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of 42 studies including 102 984 youths, the incidence of type 1 diabetes was higher during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with before the pandemic.

Meaning

The findings suggest the need to elucidate possible underlying mechanisms to explain temporal changes and increased resources and support for the growing number of children and adolescents with diabetes.

Abstract

Importance

There are reports of increasing incidence of pediatric diabetes since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the limitations of individual studies that examine this association, it is important to synthesize estimates of changes in incidence rates.

Objective

To compare the incidence rates of pediatric diabetes during and before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data Sources

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, electronic databases, including Medline, Embase, the Cochrane database, Scopus, and Web of Science, and the gray literature were searched between January 1, 2020, and March 28, 2023, using subject headings and text word terms related to COVID-19, diabetes, and diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA).

Study Selection

Studies were independently assessed by 2 reviewers and included if they reported differences in incident diabetes cases during vs before the pandemic in youths younger than 19 years, had a minimum observation period of 12 months during and 12 months before the pandemic, and were published in English.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

From records that underwent full-text review, 2 reviewers independently abstracted data and assessed the risk of bias. The Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) reporting guideline was followed. Eligible studies were included in the meta-analysis and analyzed with a common and random-effects analysis. Studies not included in the meta-analysis were summarized descriptively.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was change in the incidence rate of pediatric diabetes during vs before the COVID-19 pandemic. The secondary outcome was change in the incidence rate of DKA among youths with new-onset diabetes during the pandemic.

#Results

Forty-two studies including 102 984 incident diabetes cases were included in the systematic review. The meta-analysis of type 1 diabetes incidence rates included 17 studies of 38 149 youths and showed a higher incidence rate during the first year of the pandemic compared with the prepandemic period (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.14; 95% CI, 1.08-1.21). There was an increased incidence of diabetes during months 13 to 24 of the pandemic compared with the prepandemic period (IRR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.18-1.37). Ten studies (23.8%) reported incident type 2 diabetes cases in both periods. These studies did not report incidence rates, so results were not pooled. Fifteen studies (35.7%) reported DKA incidence and found a higher rate during the pandemic compared with before the pandemic (IRR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.17-1.36).Conclusions and Relevance

This study found that incidence rates of type 1 diabetes and DKA at diabetes onset in children and adolescents were higher after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic than before the pandemic. Increased resources and support may be needed for the growing number of children and adolescents with diabetes. Future studies are needed to assess whether this trend persists and may help elucidate possible underlying mechanisms to explain temporal changes.

Introduction

Diabetes is a common chronic disease in children.1,2 Several studies have reported an increased incidence of types 1 and 2 diabetes in children since the COVID-19 pandemic.3,4 Some studies reported an association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and new-onset diabetes.5,6 However, given the challenges of ascertaining a SARS-CoV-2 infection, there are concerns about the validity of these studies. Furthermore, there is no clear mechanism by which COVID-19 could directly or indirectly lead to new-onset type 1 or 2 diabetes.7 The pathophysiology of types 1 and 2 diabetes are distinct, as are the theoretical pathways by which COVID-19 might cause them8; therefore, it is important to determine whether there has been an increased incidence rate of 1 or both types of diabetes.

The examination of diabetes incidence rates during the pandemic is nuanced because there was a preexisting increase of 3% to 4% in the annual incidence rate of type 1 diabetes reported in European countries,9 seasonality to diabetes incidence,10,11 and variability in the reported incidence rates between early and later months during the pandemic.12,13 It is important to establish whether the reported increased incidence rates of new-onset diabetes in children are overall higher and sustained or a result of a catch-up effect from a lower incidence rate early in the pandemic likely due to delays in diagnoses.7,14

A recent review and meta-analysis4 that pooled results of 8 studies reported that the incidence rate of type 1 diabetes was higher during the pandemic in 2020 (32.39 per 100 000 children) compared with the same period prior to the pandemic in 2019 (19.73 per 100 000 children). An important limitation of that meta-analysis is that it only included studies conducted during the first wave of the pandemic. There may have been a lower incidence rate early in the pandemic and a higher incidence rate later in the pandemic due, in part, to the absence of an expected seasonal decline in summer months.12 Importantly, the meta-analysis4 only examined the incidence rate of type 1 diabetes in children. It is plausible that the increase in sedentary behavior observed during the COVID-19 pandemic due to school closures and lockdown measures was associated with the increased prevalence of childhood obesity, a known risk factor for type 2 diabetes.15,16 In addition to reports of an increased incidence rate of diabetes, there have also been consistent reports of an increased risk of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), a preventable and life-threatening condition, at diabetes onset in children during the pandemic.4,17,18

It is critical to know whether there was a sustained change in the incidence rates of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes in children because there are important implications for health resource planning for pediatric diabetes care, COVID-19–related and future pandemic-related public health measures, and immunization strategies. The primary objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to investigate whether there was a change in the incidence rate of types 1 and 2 diabetes in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with before the pandemic. The secondary objective was to assess whether there was a change in the incidence rate of DKA among youths with new-onset diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

We prospectively registered this systematic review and meta-analysis on the PROSPERO database. The study followed the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) reporting guideline.19

Data Sources and Search Strategy

We searched Medline (all segments), Embase, the Cochrane database, Scopus, and Web of Science for studies published from January 1, 2020, to March 28, 2023, in English. Our search strategy included subject headings and text word terms for COVID-19 and (diabetes type 1 or 2 or diabetic ketoacidosis) and incidence (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). We also conducted a gray literature search to identify studies published on government websites by searching for a combination of COVID and diabetes and statistical terms. We hand-searched the reference lists of all included studies and relevant systematic reviews.

Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included if they (1) reported the number of incident cases of type 1 or 2 diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic and before the pandemic in children and adolescents younger than 19 years, (2) had a minimum study period of 12 months prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic, and (3) were published in English. Two reviewers (D.D., J.E.) used Covidence software20 to determine study eligibility. Conflicts were resolved by consensus or, if needed, in discussion with a third reviewer (R.S.). Interrater agreement at the screening and full-text stages was 95% and 90%, respectively.

Data Extraction

We extracted the number of incident types 1 and 2 diabetes cases, study population size, and incidence rates of types 1 and 2 diabetes and DKA at diabetes diagnosis in the prepandemic and pandemic periods. The start of the pandemic period was defined according to the definition in each study. Two independent reviewers (D.D., J.E) extracted the data. Conflicts were resolved by consensus. Intercoder agreement was greater than 95%.

Risk of Bias

We used the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Exposure21 tool to assess the risk of bias in 7 domains (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). Two independent reviewers (D.D., J.E.) assessed the risk of bias for each of the included studies; conflicts were resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer (R.S).

Statistical Analysis

We included studies in the meta-analysis if they reported the number of incident diabetes cases and the size of the study population for a minimum 12-month prepandemic period and a 12-month pandemic period. If those data were not reported, we contacted the corresponding author, requesting for them to share the data. If the study did not report the denominator (ie, study population) and we were unable to obtain it from the corresponding author, we included the study in a descriptive summary but excluded it from the meta-analysis because studies with missing denominators are likely to be of lower quality and, therefore, are not missing at random.22 Also, we wanted to focus the meta-analysis on the highest-quality studies. Studies with both pediatric and adult participants but no subgroup analysis for individuals younger than 19 years were included in the descriptive summary.

The number of incident cases and the size of the study population during the 12 months preceding the start of the pandemic period and the first 12 months following the start of the pandemic period were used to calculate the incidence rate ratio (IRR), the pooled IRR, and the corresponding 95% CIs. We conducted a meta-analysis of IRRs using common and random-effects approaches. Statistical heterogeneity was measured using the I2 statistic, and we assessed the statistical significance of between-study variation using a 2-sided P value of <.05.

Although some studies reported diabetes incidence for longer than 12 months in the prepandemic period, we included only data from 12 months preceding the start of the pandemic period in the meta-analysis because prepandemic diabetes incidence is known to have followed a seasonal pattern.23,24 Studies that had pandemic periods longer than 12 months are described in the narrative summary. Because seasonality changed during the pandemic,23,24 we conducted a post hoc additional analysis including only studies that reported more than 12 months of pandemic data, in which we compared incidence in the 12 months before the pandemic vs the first 12 months of the pandemic vs the second 12 months of the pandemic or the end of follow-up, whichever came first. We used the meta package in R, version 4.2.2 (R Project for Statistical Computing) for data analysis.25,26

Results

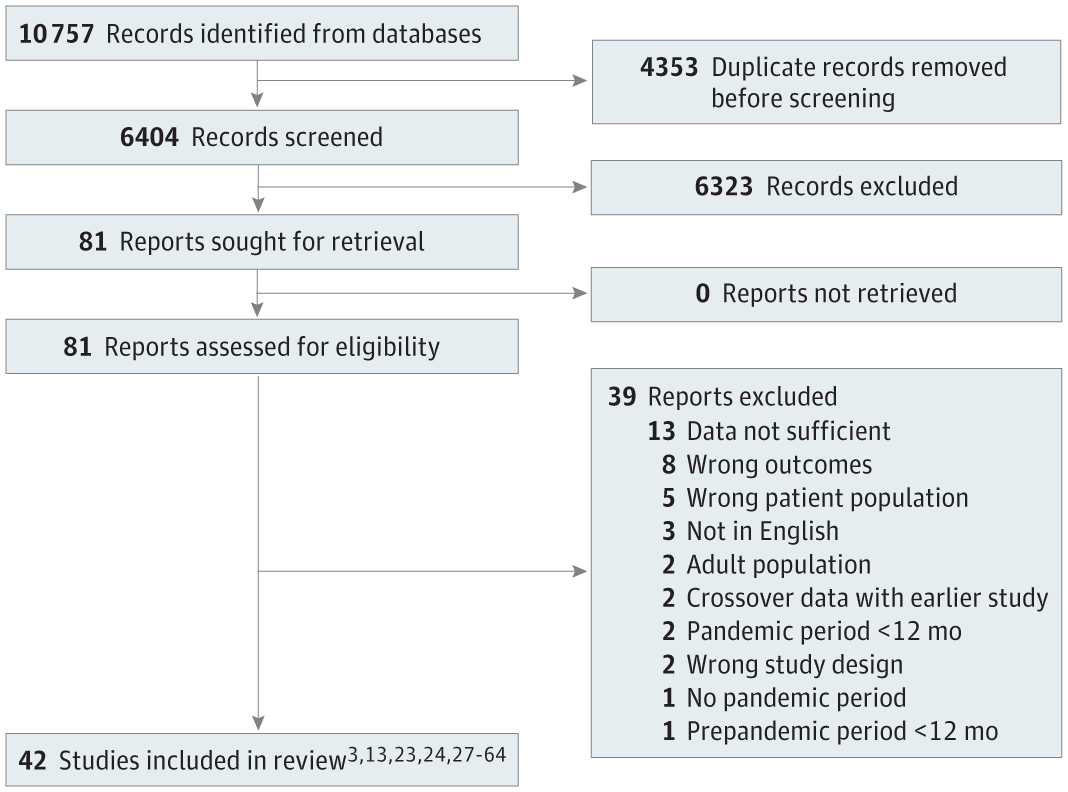

We identified 10 757 records, of which 4353 were duplicates (Figure 1). After the abstract review, we retrieved 81 full-text articles to determine eligibility. Forty-two records met the full inclusion criteria.3,13,23,24,27-64 The manual search of the included studies’ reference lists did not yield additional studies.

Study Characteristics

Among the 42 included studies, there were 102 984 incident diabetes cases across both the prepandemic and the pandemic periods (Table 1). Twenty-four studies (57.1%) reported DKA incidence at diagnosis.3,5,6,8,9,12,14,18,19,22,25,27-31,34,35,37,38,40,42,48,49 Incident cases of type 1 and type 2 diabetes were reported in 36 studies (85.7%)12,23,24,27-33,35-42,44-56,58-61,63 and 9 studies (21.4%),3,33,34,39,43,45,46,55,62 respectively. Two studies (4.8%) did not distinguish between diabetes types.13,57 Thirty-two studies (76.2%) included children only,3,12,13,23,24,27-32,35-42,44,48-53,56-58,60,61,63 while the rest (10 [23.8%]) included both children and adults.33,34,43,45-47,54,55,59,62 Twenty-one studies (50.0%) were from Europe,12,23,30-32,35,41,42,44,47-53,56,58,59,61,63 12 (28.6%) from North America,3,13,33,34,38,39,43,45,46,54,57,62 7 (16.7%) from Asia,27-29,36,37,40,60 and 1 (2.4%) from Australia55; 1 study (2.4%)24 included data from multiple countries across different continents. Nine studies (21.4%) reported either the race or ethnicity of the study population,3,34,39,43,45-47,54,62 and 1 study reported socioeconomic status.29 All included studies were assessed to have an overall risk of bias rating of “some” (eTable 3 in Supplement 1).

Type 1 Diabetes Incidence Rate and Meta-Analysis

In a random-effects meta-analysis of pooled data from 17 studies (40.5%) including 38 149 children and adolescents with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes, there was a higher incidence rate of type 1 diabetes during the first year of the pandemic period compared with the prepandemic period (IRR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.08-1.21) (Figure 2A).13,23,24,27,31,32,38,39,49-51,53,55,58-60,63 We excluded 2 studies12,65 from the meta-analysis because they contained overlapping data with more recent studies included in the meta-analysis. The data used to calculate the IRRs are available in Table 2. The unadjusted pooled IRR comparing the first year of the pandemic with the prepandemic period was 1.13 (95% CI, 1.11-1.16). Between-study heterogeneity was moderate (I2 = 66%).22 In our post hoc additional analysis, among studies that reported more than 12 months after pandemic onset, there was an increased incidence of diabetes during months 13 to 24 of the pandemic compared with the prepandemic period (IRR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.18-1.37) (Figure 2B).23,32,49,52,53,58-60,63 The results of the remaining 20 studies, which reported the number of incident type 1 diabetes cases but were not included in the meta-analysis because they did not report the size of the study population, are summarized in Table 3.24,28-30,33,35-37,40-42,44-48,54,57,61,64 Of these, 15 (75.0%) reported an increase in the number of incident cases of type 1 diabetes during the first 12 months of the pandemic compared with during the 12 months before the pandemic.33,35-37,40-42,44-48,54,61,64

Type 2 Diabetes

Ten of 42 studies (23.8%) reported the number of incident type 2 diabetes cases3,33,34,39,43,45,46,55,57,62; however, only 1 of those (10.0%) reported the size of the study populations.55 Therefore, we were unable to conduct a meta-analysis comparing the incidence rate of type 2 diabetes between periods. We summarize the results of these studies in Table 3. Eight studies (80.0%) reported an increase in the number of incident cases of type 2 diabetes during the first 12 months of the pandemic compared with during the 12 months before the pandemic.3,33,34,39,43,45,46,62

DKA Incidence Rate Meta-Analysis

In a random-effects meta-analysis of pooled data from 15 studies (35.7%) including a total of 4324 children and adolescents with DKA, the incidence rate of DKA was higher during the pandemic period compared with the prepandemic period (IRR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.17-1.36) (Figure 2C).27,29,36,37,40-42,44-47,49,50,54,65 Between-study heterogeneity was minimal (I2 = 0%).

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, in 17 studies including 38 149 children and adolescents with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes,13,23,24,27,31,32,38,39,49-51,53,55,58-60,63 we found that the incidence rate of type 1 diabetes was 1.14 times higher in the first year and 1.27 times higher in the second year after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic compared with before the pandemic. In 15 studies including a total of 4324 children and adolescents with DKA,27,29,36,37,40-42,44-47,49,50,54,65 we also found that the incidence rate of DKA at diagnosis was 1.26 times higher in the first year after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic compared with before the pandemic. The magnitude of increase in the incidence rate of type 1 diabetes that we observed after the onset of the pandemic was greater than the expected 3% to 4% annual increase in the incidence rate based on prepandemic temporal trends in Europe.9

Our findings are similar to those of another recent meta-analysis by Rahmati et al4 that examined the incidence rate of type 1 diabetes and ketoacidosis in children during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and during the same period in 2019. We compared the rate ratios reported in that meta-analysis by the length of their pandemic observation period. We found that studies with a pandemic period of 6 months or less had a lower estimated incidence rate compared with studies with a pandemic period of 12 months or greater (eFigure in Supplement 1). Our systematic review adds important new information because it included studies that examined the incidence of both types 1 and 2 diabetes in children and adolescents, included additional data from later in the pandemic, and required at least 12 months of observation in both the pandemic and the prepandemic periods to account for the prepandemic seasonality of diabetes incidence and changes in seasonality during the pandemic that differed between Europe and North America.23,24

We found substantial heterogeneity in the meta-analysis of diabetes incidence but not in the meta-analysis of DKA incidence. It is presumptive to assume why this occurred; however, some potential explanations include that higher within-study variation in the DKA meta-analysis may have resulted in a lower I2 value,66 and other demographic, geographical, and methodologic factors may have led to increased heterogeneity between studies in the diabetes incidence meta-analysis.

Purported direct mechanisms to explain the association between new-onset diabetes and prior SARS-CoV-2 infection include evidence that the SARS-CoV-2 entry receptor ACE2 is expressed on insulin-producing β cells, SARS-CoV-2 infection contributes to dysregulation of glucose metabolism, and individuals who have an increased susceptibility to diabetes are especially vulnerable following SARS-CoV-2 infection because dysregulated glucose metabolism and direct viral damage to β cells impairs their compensatory mechanisms, leading to β-cell exhaustion.7 However, there is no clear underlying mechanism explaining the association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and subsequent increased risk of incident diabetes.7,8 While there are reports of an association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and subsequent increased risk of incident type 1 diabetes in children using routinely collected health record data,5,6,67 there are concerns about the validity of such studies because the data sets used did not capture asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections in children. Population-based studies that reported an increased incidence rate of type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents during the pandemic did not find an increase in the frequency of autoantibody-negative type 1 diabetes12,23,68; this suggests that the increase in incidence may be due to an immune-mediated mechanism.

Proposed indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and containment measures that may be associated with diabetes incidence include changes in lifestyle, change in the pattern of pediatric non–COVID-19 infections, and increased stress and social isolation.12,69-71 It has been proposed that frequent respiratory or enteric infections in children are potential triggers for islet autoimmunity, promote progression to overt type 1 diabetes, or are precipitating stressors.72 Pandemic containment measures were associated with a decrease in viral respiratory and gastrointestinal tract infections among children.69 Given this finding, the observed increased incidence rate of type 1 diabetes during the pandemic is contrary to what would be expected based on the decrease in viral infections among children during the pandemic.

There may have initially been a catch-up effect caused by lower incidence rates of pediatric diabetes early in the pandemic, possibly due to delays in diagnoses associated with hesitancy to seek care or barriers to access care.12-14 However, the reported incidence of diabetes remained increased in studies that included data from beyond the first year of the pandemic.23,32,49,52,53,58-60,63 Furthermore, there appears to have been a disruption to the historic seasonal pattern of autoantibody-positive diabetes incidence in children.23,24 The reasons for this remain uncertain but may be related to the effects of COVID-19 containment strategies, such as lockdowns, both at the beginning of the pandemic and at subsequent times in different countries.73

There are limited data about the change in the incidence rate of pediatric type 2 diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic. The studies included in this systematic review and meta-analysis described an increase in the number of incident type 2 diabetes cases between periods but had insufficient data reported to assess whether there was also an increase in the incidence rate of childhood type 2 diabetes after the onset of the pandemic. Population-based studies that can measure the size of the study population (denominator) and therefore determine whether there has been a change in the incidence rate of type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic are needed.

We found an increased incidence rate of DKA at diabetes diagnosis among children and adolescents during the pandemic. This is concerning because DKA is preventable and an important cause of morbidity and mortality and is associated with long-term poor glycemic management.74,75 An international study that used data from 13 pediatric diabetes registries reported a prevalence of DKA at diagnosis in 2020 and 2021 that was higher than the predicted prevalence based on prepandemic years 2006 to 2019.76 A population-based study in Germany77 found that the regional incidence of COVID-19 cases and deaths was associated with an increased risk of DKA at diagnosis, suggesting that the local severity of the pandemic, rather than the pandemic containment measures, may have led to delayed health care use and diagnosis. In Ontario, Canada, there was a higher DKA rate among those who had no precedent primary care visits and a pattern of fewer emergency department visits during the pandemic,14 suggesting that delays in diagnosis of diabetes resulting in DKA may reflect hesitancy to seek care or barriers to access emergency care. Individuals living in areas with high COVID-19 positivity reported more hesitancy to seek emergency care for children.78 Therefore, hesitancy to seek care may be an important factor in the observed increased risk of DKA during the pandemic.

There is concern about widespread negative consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic for child and adolescent health inequities.79 However, relatively few studies examining changes in the incidence rate of pediatric diabetes since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic have reported the socioeconomic status, race, or ethnicity of the study population. Such information would elucidate whether health disparities in the incidence rates of diabetes and DKA widened during the pandemic.80,81

Implications

The results of our systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated an increased incidence in childhood diabetes after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The increased incidence rate of type 1 diabetes appeared to persist beyond the first year of the pandemic; this has important resource implications given the limited personnel resources in pediatric diabetes care to provide initial diabetes education at diagnosis and for long-term care. Future studies examining longer-term trends of incident types 1 and 2 diabetes may assess whether the increased incidence rate of type 1 diabetes continued and whether there was an increased incidence rate of pediatric type 2 diabetes. A better understanding of the possible direct effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection and the indirect effects of pandemic-related containment measures on incident diabetes in children is needed.

The increased prevalence of DKA at the time of diabetes diagnosis brings to light the need to identify the gaps in the pathway from the time when children develop signs of diabetes to subsequent diagnosis with DKA. This knowledge is needed to inform the development and implementation of effective strategies to prevent DKA at diagnosis in children. These may include public and health care professional–facing awareness campaigns and addressing hesitancy to seek emergency care.78,82

Limitations

This study has limitations. Our search was restricted to studies published in English, and the included studies did not represent all regions of the world, limiting the generalizability of our findings worldwide. We included only studies that reported the incidence of DKA at diabetes diagnosis among studies that met our eligibility criteria, which required reporting incident diabetes cases in both study periods. Some studies included in our systematic review did not measure diabetes autoantibodies to confirm whether an individual had type 1 or another type of diabetes; thus, there may be a risk of misclassification of diabetes type.

Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis found increased incidence rates of type 1 diabetes and DKA in children and adolescents during vs before the COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings underscore the need to dedicate resources to supporting an acute increased need for pediatric and ultimately young adult diabetes care and strategies to prevent DKA in patients with new-onset diabetes. Although prospective data examining whether this trend has persisted are needed, our findings suggest the need to elucidate possible underlying direct and indirect mechanisms to explain this increase. Furthermore, there is a paucity of data about socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic disparities in the incidence rate of diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic; this gap must be filled to inform equitable strategies for intervention.

The paper isn’t paywalled: