This is absolutely just her drumming up a case for intervention. She sees China’s B&R as an existential threat to the US and see the entirety of South America as nothing more than raw material.

Chinese investment is really extraction, Richardson said. Not just in terms of cash or natural resources, but also strategic positions. The general described a recent flight over the Panama Canal where she saw Chinese state-owned enterprises on both sides of the canal that could be turned quickly toward military capabilities.

“I think we should be concerned, but this is a global problem,” she said.

First Principles or Axioms would be the terms you’re looking for

Started (at least in Western science) with Euclid’s Elements:

All of these are taken as the base assumptions for the rest of the logical proofs for euclidian geometry.

With physics, I’d say the thermodynamic laws are the axioms.

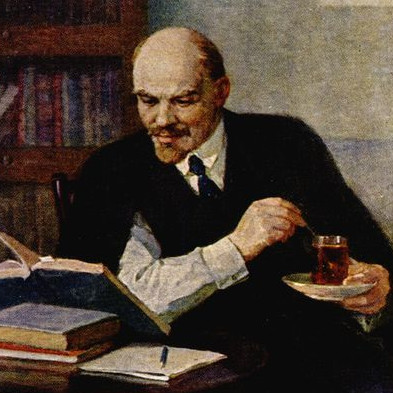

With political science, the axioms aren’t as clearly defined. Marx and Engels are really the first to try and lock them down with the concepts of class struggle and Labor == Value (“all history is the history of class struggle” is one of Marx’s big axioms). Marx also uses thermodynamic principles in the context of political economy with Labor standing in for energy.